Hinduism is the dominant religion in India as shown by its name; people do not become Hindus but are born as Hindus. The word Hindu is originally derived from the River Sindhu in Sanskrit (Indus in English), from which the S-sound dropped out, used by Persians to indicate the people living along and over the Indus. The area was called Hindustan (the country of Hindus) or Indos in Greek, and its language Hindi and religion Hinduism as well.

Though considered as a religion, Hinduism is different from the Western notion of religion, rather being the living system of the Indians in a broad sense, including their social customs, conventions and manners.

1. WHAT IS HINDU ARCHITECTURE ?

Hinduism did not have a particular founder as in Christianity or Islam. It subsumed every phenomenon in the vast territory of India, including even local faiths and tribal gods, so they could even be contradictory to each other. According to Hindu theory, even Buddhism and Jainism are nothing but sects of Hinduism.

In the field of architecture too, those of Buddhism and Jainism, which were brought up in the same climate as that of Hinduism, have no great disparities from Hindu architecture, making it possible to say that their structural systems and forms of their components are completely the same.

However, if Hindu architecture is geographically positioned as Indian architecture, it would mean that Hindu architecture could not exist outside India. In order to avoid this inconvenience, I will not adopt a geographical definition but treat it on the basis of religious and historical distinction from Buddhist, Jain, and Islamic architecture. On this occasion, secular buildings, such as residences, palaces, forts and others, must be excluded, that is, Hindu architecture in this article indicates only Hindu temples.

2. THE ESSENCE of HINDU TEMPLES

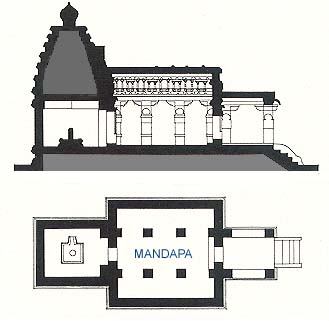

Principal Plan and Cross Section of a Hindu Temple

(Malikarjuna Temple in Aihole, 8th century)

iFrom "Encyclopaedia of Indian Temple Architecture" II-1, 1988 j

The predecessor of Hinduism is called Brahmanism, in which only Brahmans (priests), the highest class among four varnas into which people were divided by birth in ancient India, could intermediate between gods and believers. It was essentially a religion of rituals emphasizing sacrifices of animals to gods.

On the other side, Buddhism and Jainism were atheistic religions established around the 6th century B.C.E. in contradiction to the caste system and the sacrificial practices of Brahmanism, so their temples were fundamentally places of pursuing enlightenment for monks and expounding teachings to lay people.

Hinduism, which was established around the beginning of the Common Era, was a highly developed stage of Brahmanism in preparedness for theoretical dispute. Absorbing folk faiths and local divinities in various regions, it was a thoroughgoing pantheistic religion based on, above all, reverence for the gods that originated in the Vedas. Every Hindu temple has one of those gods enshrined as the main deity, and is as hospitable to it as if it were a living personality. The essential quality of the Hindu temple is the eHouse of Godf, though it differs from the metaphorical manner in the Christian church, as a Hindu temple is considered as an actual place for a god to dwell, eat, and sleep.

The cardinal room, where is the statue is set into which a god is to enter, was called a eGarbhagrihaf literally meaning a ewomb housef, and its frontal hall, where priests and followers entertain and worship the god, was called a eMandapaf, then became the fundamental form of Hindu temples.

3. CAVE TEMPLES and ROCK-CARVED TEMPLES

Unfinished rock-carved temple

It is presumed that ancient India was abundant in wood and most temples were built of timber, though none have survived. The ancient architecture that we can see now is made up of cave temples, which were excavated into rocky mountains and architecturally carved in detail. This form was initiated by Buddhist monks and workers, executing as many as a few hundred in number from the 2nd century B.C.E. across India.

The oldest Hindu cave temples are a small group at Udayagiri from the 5th century of the Gupta Dynasty, where many of the earliest Hindu sculptures are also extant. Because in this age integral stone buildings, moving out of the phase of mixed structures of timber and stone, began to be constructed, cave temples were to develop hand in hand with stone architecture. The plan form of was also established through this process, as can be seen in the Hindu cave temples of Ellora, excavated in the 7th and 8th centuries, most of which took this form.

On the other hand, since the Hindus preferred sculpture more than any of the formative arts, they wanted to make even their architectural works as if sculptures. Monolithic temples, sculpted not as caves but directly upon one rock in the round in this attitude, are called erock-carved templesf. Started in Mahabalipuram in the 7th century, it attained its apogee in the Kailasa Temple at Ellora in the 8th century. Such a sculptural character in Indian architecture would stay as the fundamental feature in later stone temples too.

4. WAYS of SOLEMNIZING TEMPLES

Plan of the Gondeshvara Temple in Sinnar, in the Pancha-yatana Form

iFrom the "Mediaeval Temples of the Dakhan" by Henry Cousens, 1931j

Plan of the Gondeshvara Temple in Sinnar, in the Pancha-yatana Form

iFrom the "Mediaeval Temples of the Dakhan" by Henry Cousens, 1931j

Although simplest Hindu temples did not have Mandapas, constituted of only a Garbhagriha (sanctum) accompanied with a porch, they gradually increased in scale, in accordance with the establishment of the form . The Garbhagriha itself did not enlarge, because it is a square room enclosed with windowless thick walls, but extended its plan, encircled with a circumambulatory corridor for worship, and it came to be surmounted with a stone piled tower, displaying its sculptural exterior view.

The Mandapa, in front of the Garbhagriha, was also fundamentally a square hall with four pillars, occasionally becoming a great hypostyle hall.

In order to solemnize temples, architects often increased the number of Mandapas, placing them in a line in the front, and occasionally added an open Mandapa without peripheral walls, the porches, and even an independent shrine for a Nandi (bull), vehicle for Shiva, all in line on the axis.

The reason for this manner is that a Hindu temple was destined to have a determined axial direction, following the fact that Garbhagriha as a godfs abode had only one entrance door in front to be locked at night. This restriction made the temple impossible to spread in four directions, and engendered another method for the solemnization of temples, adding four small independent shrines in four diagonal corners on the podium, giving the entire temple the form of Pancha-yatana (five shrines).

5. THE NORTHRN and SOUTHERN TYPES

Vishvanatha Temple of the Northern type, Khajuraho

Through the great development of Hindu temple architecture in the medieval period, rivalling stone architecture in Europe and the Middle East, its style was roughly divided into two: the Southern Type and Northern Type. It might have reflected the differences of likings between northern Indo-Aryans and southern Dravidians, languages of which were in completely different branches.

The item that shows the difference between them most clearly was the design of their towers over the sanctuary.

In the Northern Type, the tower soars in the shape of an artillery shell, which is called a eShikharaf. On the top of the Shikhara is a fluted disk, an Amalaka, imitating the shape of a sacred fruit, Anmalok, and further on top of it is a pitcher-like finial, a Kalasha. Similar small Shikharas with the same components are piled up to make a greater Shikhara, repeating this cycle in several layers to form the whole intricate body.

As opposed to this, in the Southern Type, lined mini-shrines make a horizontal story and many stories piled up in steps form a pyramidal tower. On top of it is a large hemispheric or octagonal dome-like crown stone, which is called a eShikharaf in southern India, literally meaning a mountain summit in Sanskrit.

Among the Southern Type temples, the Karnataka region engendered star-shaped plans for Garbhagrihas and a unique form composed of several Garbhagrihas and a shared Mandapa, displaying their towers in the intermediate shape of the Northern and Southern Types.

6. CORRESPONDENCE to CLIMATE

A Himalayan woodenTemple at Sungra

Although the Indian subcontinent belongs to the zone of monsoon to a large extent, its large geographical expanse includes diversity from the cold district of the Himalayas to southern India in the subtropical zone through arid western India embracing a great desert. Hindu temples have also a wide variety corresponding to those climates. The foremost element bringing about the variation is the building materials.

Central India, possessing a large number of sturdy rocky mountains, became the most crowded area for cave temples. The delta regions along the Indus in the west and the Ganges in the east do not produce stone of good quality, so brick has been used as the main material since the time of the Indus Valley Civilization. Brick temples in Bengal covered with terra-cotta panels, baked with carvings executed on not fully dried clay, dyed villages the color of Indian red.

Wooden temples descended from ancient architecture to some extent are seen in the Himalayan region in the north and the Kerala region in the south, both of which are blessed with much precipitation and forests. Especially in mountainous Himachal Pradesh there are curious wooden temples surmounted with conical or gambrel roofs, completely different in shape from stone temples in the lower Indian planes.

However, what underlies these wooden temples is the composition of ; there is no difference between these and stone temple in indicating the abode of god by its wooden eShikharaf on a small chamber.

7. OUTWARD from the INDIAN SUBCONTINENT

Lorojonggrang Temple at Prambanan, Java, Indonesia

Indian culture was propagated to Southeast Asia mainly through trade. Hindu architecture was brought to Burma (Myanmar), Khmer (Cambodia), Champa (Vietnam), and Java and Bali (Indonesia) in indistinguishable forms from Buddhist architecture. In this process, it produced various transfigurations according to the traditions and climates.

The best representative example is the Lorojonggrang Temple at Prambanan, Java, dedicated to Shiva. Partly because of the ancient custom of ancestor worship in Java, a ehouse of godf also came to have the character of a mausoleum for forefathers. This is probably the reason why most temples were not accompanied with Mandapas but a porch only, located in the center of its podium. The form of their towers was based on the Southern Type, in which horizontal floors were piled up in steps.

Khmer architecturefs transfiguration is best shown in the Angkor Vat, in which the temple and kingfs tomb were united in one, conforming to the eDeve-Rajaf (god-king) philosophy, constructing its precincts on a vast scale than ever existed in India, on a square plan like an enlarged form of Mandala.

It was made possible by the grace of the form of the Chaturmukha (four-faced shrine) plan developed in Jain temples, which was brought to Southeast Asia along with Hindu architecture. As a result, in contrast to Hindu temples in India, those in Southeast Asia could spread in four directions, forming great Mandala-like plans. In the Garbhagriha of the Angkor Vat, as a four-faced shrine, there would have been enshrined the God Vishnu. Its tower is thought to have originated from the artillery shell shape of the Northern Type.

|