| PLAY in INDIAN ARCHITECTURE |

TAKEO KAMIYA

| PLAY in INDIAN ARCHITECTURE |

TAKEO KAMIYA

Architects sometimes say gthis part is playh, when they make some shapes or employ some ingenious device to give viewers a feeling of pleasure or curiosity over and above the bare functions of the buildings that they are designing. However, when formally considering what the play in architecture is, it is difficult to recall typical examples of earchitectural playf.

Buildings are projected in order to meet certain strong needs, and architects, a normally serious species, are immersed day and night in how amply they can create convenient and comfortable buildings on a limited budget. They do not often play at the expense of their clients unless the building is for the function of playing itself, such as amusement parks or game rooms.

When it comes to Indian architecture, one would recall Hindu temples decorated with innumerable sculptures, and suppose that play must be plentifully enjoyed in Indian architecture. However, most of those sculptures, such as statues of deities, are means of edification of religious tenets; even Mituna statues (sexual coupling) are explanations of a doctrine of Hindu Tantrism. They bear a practical function, and cannot be called pure play.

An example expressing play more clearly is seen in a wall panel at the Hindu temple of Mukteshvara in Bhubaneshwar, shown below.

Bhubaneshvar, 10th century

However, if I were asked whether the above-mentioned examples are real eplay in architecturef, I would reply that I do not think so. Both of those temples are orthodox pieces of architecture, seeming not to playing so much, that is, their play is nothing but esculptural playf. There is the Mausoleum of the saint Salim Chishty in the grand courtyard of the Great Mosque of Fathehpur Sikri, the abandoned Mughal capital near Agra. One can recognize that this renowned buildingfs walls make geometric patterns combining white marble and blackish stone, but when going inside and looking back at the wall, one realizes that the stone that looked blackish is actually a delicate screen of the same white marble. It is, so to say, a magic stone wall, looking only like a blackish solid stone as an exterior view, impossible to see through from the outside, but possible from inside, out to the courtyard.

Mausoleum of Salim Chishty, Fathehpur Sikri

Although those stone panels can be imagined being quite vulnerable, having been made so delicately, they are actually very sturdy marble boards of 5 to 10 cm in thickness, drilled in a systematic pattern. It is as strong enough as to not break even if strongly kicked.

Then, how about the case of the Mausoleum of Humayun? This enormous tomb of the Mughal emperor in the capital Delhi is completely covered with marquetry of red sandstone and white marble. This elaborate method in stone architecture, equivalent to Byzantine mosaics, is the technique that was most highly developed in Mughal architecture.

@ @Mausoleum of Humayun and Jantar Mantar, Delhi

When pursuing examples of play not in finishing but in architectural form itself, the buildings of the Jantar Mantar (observatories) are recalled. Although their unique singular forms, still extant in Jaipur, Delhi, Banaras and other places, are so extravagant as to make German Expressionist works inconspicuous, they are also not play but practical forms.

As we saw in the above sections, it is quite difficult to find examples of play in architecture itself in India. Then, is there nothing at all around the world?

The famous Romanesque abbey, Santo Domingo de Silos, in northern Spain has a magnificent courtyard encircled with beautiful cloisters. A compound pillar of four columns in the west cloister is conspicuous because of being twisted; those columns are all slanted as if the masons had carelessly set their tops and bottoms at wrong positions, giving a quite eccentric posture to the pillar.

@ @Cloisters of the abbey of Santo Domingo de Silos

Although it is a surprise that such a joke or play is done in a monastery, which normally would be quite austere, one can notice that similar behavior in architecture is seen in various places during a tour of Romanesque architecture in Europe; some columns bend or meander like spaghetti and others buckle as if they cannot sustain a too heavy load.

Though there are a large number of examples of play in sculptures in India, I know of no examples of making a joke in the primary elements of architecture.

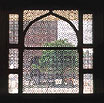

Window screens of the Sanprati Raja Temple, Girnar

Given this viewpoint, plenty of examples of eplay in architecturef can be instantly recalled. Typical examples are the Derwara Temples in the bosom of Mt. Abu and the Adinatha Temple soaring alone among deep mountains at Ranakpur. An example of this principle applied to windows is in the Sanpraty Raja Temple on Mt. Girnar, in which play can be seen in all the window screens of different patterns. Moreover sculptures on the domical ceilings of the temples on Mt. Abu are enormously complex and delicate beyond imagination; according to tradition, sculptors were paid in proportion to the amount of marble that they carved off, so they carved more and more intricately.

A domical ceiling at Mt. Abu and pillars of the Vitthala Temple Such spectacular architectural components can be seen above all in the architecture of Vijayanagara, the last Hindu dynasty in southern India, as seen in the above photograph of the Vitthala Temple, every pillar of which is carved out so fantastically and endlessly, in a way that cannot be found other than in India throughout the world. This extreme world, mixing religious passion and artistic eagerness, seem to have fallen into a slight decadence beyond the spirit of play.

If one supposes that temples and palaces are always decorated brilliantly, so they are not eplay in architecturef, I can show a yet more astonishing example: the stepwells existing mainly in the state of Gujarat, western India.

@ @Stepwell at Adalaj, India, and Khaju Bridge in Isfahan, Iran

It is a piece of underground architecture; one can see only an entrance part on the ground, and all the the other parts were constructed below the ground. The perspective view of its subterranean framework of columns and beams emerging in the dark, bathed in the light from the sky, is quite fantastic. |