|

TRAVELS in 2001 & 2010 to

|

TAKEO KAMIYA

|

TRAVELS in 2001 & 2010 to

|

TAKEO KAMIYA

I traveled in Pakistan for the second time this spring to research various kind of architecture; Buddhist, Islamic, and colonial. Here I will write on the wooden Islamic architecture in the Swat Valley and the masonry one in the Multan district.

Since I was fascinated by wooden architecture in Himachal Pradesh in northern India, I had been wondering whether that culture continued to the northern part of Pakistan across Kashmir region. As I could not afford to visit Gilgit and Skardu districts in Pakistan this time, I settled on researching wooden architecture by going upstream of the Swat Valley from Peshawar.

A unique characteristic of Himachal architecture in India is the walls piled up with timber and stone layers alternately to resist earthquakes' horizontal forces. Such a structural system is hardly seen in the adjacent Kashmir region, but its existence in the remote Nuristan region in Afghanistan had been confirmed in the book, Albert Szabo's "Afghanistan, An Atlas of Indigenous Domestic Architecture." Then, what about in between in Pakistan was my main interest.

As a result of observations and books, I became acquainted with that method being main stream in the past in the Swat Valley too. Old mosques and houses had no columns except for on balconies, but made their walls by stacking wooden frames as horizontal components and filling with stones in between.

Old and New Jumat (Friday Mosque), Madyan

The first town to meet in the Upper Swat Valley, which is also referred to as Swat Kohistan, is Madyan. There ought to have been a Jumat (Friday Mosque), the courtyard of which would have been surrounded by wooden hypostyle halls. Turning into the old quarter from the thoroughfare under children's guidance, I arrived there and found in surprise a newly constructed mosque with concrete painted brightly. Unfortunately just four years before, it was rebuilt, changing the structure from timber to concrete. Nevertheless an antique townscape of wooden houses still remains in the old quarter around the mosque. The most magnificent private house is the century old Subedar House, the columns and portal of which are carved delicately. I especially paid attention to the columns' brackets, on which two or three scrolls are carved each. On the entrance door there are curvings similar to the column's two stretching arms form as a decoration. I would gradually comprehend that is an architectural leitmotif in the Upper Swat.

Portal and its Wood Carving of Subedar House, Madyan

Next to Madyan is the small town of Bahrain, where there also ought to have been a wooden mosque. However this mosque too has been demolished and rebuilt in concrete, what is more all the timber columns and wall panels were sold. What on earth has the Archaeological Survey of Pakistan been doing? Are they only looking on with folded arms whilst such a precious cultural heritage is being lost? Going upstream on the Swat River, I arrived in Pishmal where I could visit a wooden mosque at long last. It has a peculiar minaret with a single timber column, as if it were a birdcage. I was told that not one wooden minaret with a spiral staircase remains in Pakistan.

Exterior and Interior of the Wooden Mosque, Pishmal

The structure of this mosque is periphery walls piling timbers and stone layers alternately and two enormous wooden pillars as thick as a meter standing outside of the eastern wall and at the center of the worship hall. Those pillars extending their brackets with three continuous scrolls each on both sides and supporting an enormous girder have an overwhelming presence.

Jumat (Friday Mosque) in Kalam

The deepest of the Swat Valley towns is the town of Kalam, at an altitude of 2,070m. As a bustling summer resort It has many new hotels, but to my disappointment there was not even an old quarter, having lost all trace of a kingdom of the days gone by.

Incidentally it surprises us as at Pishmal that this mosque also is divided by a wall into two separate halls, each of which has a Mihrab in the direction of Makka. In spite of a first feeling of confusion as to which is the main worship hall, actually one is a summer mosque and the other is a winter mosque. A summer mosque is usually open to its courtyard, through which breezes go, while a winter mosque is closed and provides a large stove to warm up. In short, these are the double mosques in a cold region that are hardly seen in other regions in a vast extent of Islamic world.

Another major objective of this travel was to photograph the early Islamic legacies left in the Multan region in central Pakistan. Though it was in the early 13th century that the first Islamic political power was established in Delhi, India, it was from the 8th century that Islamic armies repeatedly invaded what is currently Pakistan. The 14th century when characteristic Islamic architecture flourished in Pakistan corresponds to the age of the Tughluq Dynasty, the second Delhi sultanate in India.

It soars in large precincts accompanied by a small mosque, showing a harmonious whole with a lot of elaborated details. It is said that was erected by the sultan of the Tughluq Dynasty in Delhi, Ghiyath-ud-Din, who built his own mausoleum too at almost the same period in Tughluqabad, a southern suburb of Delhi. Actually those two are quite similar iwith their inclined massive walls with few apertures and the white bulky domes, as the early works of Islamic architecture in South Asia. In therms of visual effect, instead of simple and cubic shape in Delhi, they established an excellent style in Multan, piling two octagonal layers, making a turret stand up on each corner, and covering the top with a great dome. On the whole, it can be said Multan might be superior to Delhi.

Dome and Interior of Sheikh Rukn-i-Alam

Inside of the mausoleum tombs are densely gathered; the large one of the Sufi saint, Rukn-i-Alam and other small tombs. Though this building seems like two storied from outside, the inside of it actually is a single voluminous space with a great dome on top, from the drum of which high-side-lights fall. Making a 16 sided polygon by circularly continuing pointed arches on the thick walls of its octagonal plan, then converting it into a thirty-two-sided polygon (almost a circle) above that, the whole forms a superb transitional zone from its octagonal body to the hemispherical dome.

As Uchch, 140 km south of Multan, is a sacred town possessing a celebrated Dhargah (Sufi saint's mausoleum), it is referred to as Uchch Sharif too. The main buildings are a complex of a mausoleum of a saint in the Suhrawardi order, Jalaluddin Surkh, and a mosque. Both of them are wooden buildings in spite of the outer appearances of brick walls. Once inside the mausoleum, one finds a breathtaking interior with a forest of wooden columns supporting joists by their sculptural brackets and painted delicately.

Shrine of Jalaluddin Bukhari

A bit strangely, the main tomb, which has a canopy, among tombs settled in rows is not positioned on the central axis from the entrance, but quite deviated to the western side. Therefore, as seen in the above photo, the passage from the entrance to the main tomb is winding. It resembles Japanese aesthetics in avoiding central axes deliberately, but the true reason is unclear.

There are three dome-type mausoleums near here, on the mound of the old fort. The mausoleum of Bibi Jawindi from the 15th century follows the Multan style, covered on top with a large dome with turrets on each two-tierd corner of the octagonal edifice.

However, when looking from behind, we are surprised to find the rear half of this edifice has been completely lost. Actually, the flood of the Sutrej River destroyed it together with the upper parts of the turrets in 1817.

Front and rear sides of Mausoleum of Bibi Jaundi, Uchch

In a dome structure made of stones or bricks piled radiately, a force that is referred to as 'thrust' operates to widen the span toward its final collapse. How to resist and annihilate this thrust is the skill of arch builders.

Close to this Bibi Jawindi Mausoleum two other mausoleums stand in half collapsed state too. One of them is dedicated to an architect by the name of Nauria, who designed the other two mausoleums.

( 10/ 07/ 2001 )

TOP

Nine years after the above-recounted journey, I again traveled to Pakistan, visiting relatively southern areas this time. India, which Pakistan considers a competitor, has seen vast economic development over the past 20 years, becoming, along with China, a major economic power, while Pakistan has fallen greatly behind, giving one an impression of almost stagnation.

Pakistan has suffered various misfortunes: repercussions from neighboring Afghanistanfs upheavals, invasions by Islamic extremists, frequent occurrence of terrorist incidents, the governmentfs collaboration with Americafs war against terrorism and the instability of the political situation, and as a further setback, various natural disasters such as the record-breaking heavy rain and great flood in 2010.

Remains of Mohenjo-daro in the morning and day

Though not Islamic sites, I report here the current state of Mohenjo-daro and Harappa, which represent the Indus Valley Civilization. I revisited the former for the first time in 33 years, staying one night at the site as before. Though I was to get a room in the new on-site PTDC (Pakistan Tourism Development Corporation) Motel, it had been closed for some years, because almost no foreign tourists were coming. During my foreigner registration at the police office, I found in the register that I was the first foreigner in nine days. Only 1 km from Mohenjo-daro airport, all the facilities are just before the entrance to the ruins, such as the Rest House (Dak Bungalow), Museum, the Office of Department of Archaeology, and the Police Office. I stayed again at the old rest house in which I had stayed 33 years ago, and I was their first guest for some months. Time seemed to have stopped for 33 years; everything was the same as before, the room, the food, peoplefs appearances, the exposition in the museum, and the ruins. I wondered if peoplefs lives had much changed from a restored scene of the age of the Indus Civilization on a large mural drawn at the piloti of the museum.

These facilities are in the style of Le Corbusier. When constructed to the design of Michel Ecochard, the French architect, they were representative pieces of modern architecture in Pakistan, but they are now quite in disrepair after half a century has passed. As for the ruins from about 2.500 B.C.E. themselves, while excavations and restoration works were ardently implemented before, nothing has been done since the beginning of this century, making me suppose that the ancient city of Mohenjo-daro will not ever be fully elucidated forever. Now erosion by salt is proceeding in the deeper underground areas, bringing the entire remains into a critical state. I walked around the archaeological sites thoroughly without haste, accompanied by one of the site guards as a guide cum porter for my heavy camera bag. I was photographing again the excavated quarters after a lapse of 33 years, when I noticed afresh the half crumbled Buddhist Stupa giving the site a quite symbolic effect. It was constructed in the Buddhist age, the Kushan period, on the top of the citadel mound, destroying a part of the remains of Indus Civilization in fact, but if this Stupa was not there, official pictures of Mohenjo-daro would ironically be far less attractive.

Granaries quarter and a ruin of a mosque in Harappa

On the other hand, I had not visited the ruins of the Indus Valley Civilization at Harappa, although I had been hoping to go there at least one time to fully look and take photos of the site, out of sense of obligation, over a period of many years. At last I could visit Harappa, but even so I did not stay at the spot or the nearest town, Sahiwal. I chose to hire a taxi for the whole day, departing Lahore early in the morning, staying in Harappa (ruins and museum) for four hours, and arriving in Multan late in the evening. A magnificent highway connects Lahore and Multan nowadays, which one can drive through nonstop in five hours. In Harappa, there is no spot from where one can get a whole view of the ancient city, but small excavated places scattered around, so one cannot take spectacular photos. As the outcome of excavation of each place is also not abundant, it is difficult to imagine a clear figure of the original city. Some of the places, such as area F to the north of the citadel mound, which is supposed to have been made up of granaries, the foundations of which are regularly arranged, are impressive.

While there is a Buddhist stupa of later period in Mohenjo-daro, Harappa has remains of a mosque from much later ruling Islamic age in the area AB. It is not located at a conspicuous spot like the Stupa of Mohenjo-daro and only a portion is left, so it cannot be a symbolic element for photographs of Harappa.

It is Lahore, which was once the capital of the Mughal Dynasty, that holds the richest Islamic architectural heritage in Pakistan. The third emperor, Akbar the Great, moved his capital from Agra to Fatehpur Sikri, and then to Lahore, constructing a town and a fort at each location. Even after the capital was returned back to Agra and Delhi, the successive emperors continued construction in Lahore, as an important military position in the western region in India. I revisited Lahore also after an interval of 33 years. The town, which had been calm and tranquil erstwhile, had become prosperous and bustling as the capital city of the Punjab, and Pakistanfs next largest city after Karachi. However, since there are no streetcars, to say nothing of a subway, everybody relies on buses, cars, taxis, and auto-rickshaws for transportation, so their exhaust fumes, along with factory emissions, has brought about severe atmospheric pollution. Making the mistake of not wearing a gauze mask, I bitterly hurt my throat.

There are no ancient remains in Lahore but various monuments, ranging from medieval Islamic architecture to British modern colonial facilities. I will introduce here the main Islamic edifices in the city and its neighborhoods one by one. The northern part of Lahore is the old area developed in the Mughal period and its northernmost point is occupied by the Lahore Fort. It was a vast Mughal fortress to rank with the Agra and Delhi fortresses, originally surrounded with strong ramparts and moats, most of which have been demolished and filled in. A lot of palaces and gardens are arranged closely on the premises, mainly due to the fourth emperor, Jahangir, putting his Court here from 1622 to 27, and the architect-emperor, Shah Jahan, constructing many white marble palaces and mosques, as he did in Agra and Delhi.

Every garden is geometric, based on the principle of the traditional Charbagh (four quartered garden). The largest is naturally the Charbagh in front of the Diwan-e-Am (Public Audience Hall), where citizens were able to enter freely, royal declaration was shown, the emperor had audiences with courtiers and foreign envoys, and trials were conducted. As the Diwan-e-Am built by Shah Jahan embraces 40 columns, it was called eChehel Sotun (Palace with 40 columns) like a famous palace in Isfahan, Iran. Its inner rhythmical space with continuing pointed arches is a magnificent open space, suitable for the scale of a multitude of people. In the rear of this palace is Jahangirfs Quadrangle (square garden with cloisters), where Jahangirfs Khwabgah (bedchamber) and slightly modified enormous Charbagh, centering on a pond, are surrounded with cloister-like rooms. One can notice that various animal figures are carved on the brackets of the cloisters. Although images of creatures are never depicted in religious buildings, it was overlooked in palaces. Such figurative carvings are also seen at the Jahangir Mahal in Agra Fort.

Likewise, on the northern ramparts of the fort, colorful tile mosaics depict not only geometric and foliage patterns but also figurative scenes of elephants, soldiers, and so forth. Apart from miniatures and wall paintings looked at in private rooms, such figurative drawings in public places are quite uncommon. It can be said that the tradition of Indian culture before the advent of Islam would have crept into the Mughal art.

In Shah Jahanfs Quadrangle, smaller than Jahangirfs, stands the Diwan-e-Khas (Private Audience Hall) of white marble, resembling the Khas Mahal in Agra Fort, only differing in some aspects; its columns are more slender, having no Chhatris on the roof, and it is not accompanied with Bangardar roofed pavilions on both sides.

Shah Jahan, who had a deep predilection for white marble, built a small-scale Moti Masjid (Pearl Mosque) of that material as a royal oratory, not to be confused with the mosques of the same name in the Delhi and Agra Forts. However, in Agra Fort, the similar royal oratory is the Nagina Masjid (Jewel Mosque), and the mosque designated as Moti Masjid is a much larger one on high ground, having been Agrafs Friday Mosque until the Jami Masjid was constructed outside the fort. The Moti Masjid in Lahore Fort is a little difficult to find, entered not from the front but through a small flight of stairs in the flank, giving a softer feeling to the steps, which might indicate that it was a royal mosque for court ladies. Though its scale is slightly larger than the other two, consisting of five spans in width, compared to the three spans in both the Moti Masjid in Delhi and the Nagina Masjid in Agra, it is not easy to take photos because of the narrowness in the depth of its courtyard. From the point of formative art, it can also be said to be a little subdued.

Pearl Mosque, Naulakha Pavilion in the Lahore Fort

The westernmost part of the fort is an area called Shah Burj, where the Sheesh Mahal (Palace of Mirrors) stands in front of a Charbagh, but a side building called the Naulakha Pavilion is more noticeable. This is a mysterious building with the characteristic curved eaves of a Bangaldar roof, but it actually is not a real Bangaldar roof, as its inward part is flat. On the west of Lahore Fort, across the Hazuri Bagh (garden), is the largest mosque not only in Lahore but also in the Indian Subcontinent, the Badshahi Mosque. As its area is 160m by 160m in size, 100,000 people can worship together, lined up also in its vast courtyard. It was constructed by the sixth emperor, Aurangzeb. The founder of the Mughal Dynasty, Babur, called himself Badshah (Padishah, meaning Great King) while the kings of the past Delhi Sultanate had called themselves Sultans. As his successors followed this custom, Mughal kings are called emperors in English, and Jahangir named his great mosque the Badshahi Mosque. This is one of the four greatest mosques of the Mughal Dynasty, along with those of Delhi, Agra, and Fatehpur Sikri, and as it was the last one, it is on the largest scale and best preserved.

Badshahi Mosque in Lahore

While I had ascended the left minaret behind the worship hall 33 years before, this time I got permission to ascend the diagonally opposite northeastern minaret which I had desired a long time, and I was able to take photos of the mosque from the best angle from a height of 50m.

As at the Taj Mahal, these magnificent domes of white marble have no function other than as decorations intending to make the external appearance greater. The actual domical ceiling is placed at the level of the central domefs foot. White marble domes exist only in the Indian Subcontinent, likewise it can be said that the esculptural architecturef through self-display with excessively bold double-shell domes is also a characteristic product of Indian civilization. There is a group of Mughal mausoleums at a suburban village, Shahdara, across the Ravi River, 3km north of the Lahore Fort. Among the tombs of the Great Moguls, that for the second emperor, Humayun, is in Delhi, the third emperor, Akbar, is at Sikandra near Agra, the fifth, Shah Jahan, along with his wife, Mumtaz, is in the Taj Mahal in Agra, the modest one for the sixth, Aurangzeb, is at Khuldabad in southern India, and then here in Lahore is one for the fourth, Jahangir, because he loved the city of Lahore and expired here. The district called the Shahdara Complex consists of three Charbaghs; the larger square one on the east of the central rectangular Akbari Serai is for the mausoleum of Jahangir, and the western smaller square one is for that of Asaf Khan. The tomb garden of Jahangir, originally a pleasure garden called the Bagh-e-Dilkusha set up by his wife, Nur Jahan, is a vast Charbagh of 460m square in size, rivaling the Charbagh of Akbarfs tomb at Sikandra at 480m square. Although the location of the mausoleum in the center of the enormous Charbagh is the same as the cases of other emperorsf tombs, it gives some feeling of lack, due to it not being surmounted with a dome. Judging from the fact that it has as many as four minarets, which are unnecessary for a tomb, at a height of about 30m, it might have been unfinished.

Mausoleum of Jahangir at Shahdara

While the mausoleum of Jahangir was constructed by order of his son, Shah Jahan, it was designed by the empress, Nur Jahan. It is said to have been modeled after the just prior Mughal mausoleum in Agra for her father, Itimad-ud-Daulah. Asaf Khan was Nur Jahanfs brother, thus, Jahangirfs brother in law, and the governor of Punjab. As the capital of Punjab was Lahore, his tomb was set right next to the mausoleum of Jahangir. It stands in the center of a Charbagh the size of just one fourth of Jahangirfs garden. While the Persian style finishing with glazed tiles on its walls has been almost all lost, its dome seems to have been finished with white marble. The excessive bulbous shape of the dome is said to have been an alteration made in later ages.

Mausoleums of Asaf Khan and Nur Jahan at Shahdara A little distance from the Shahdara Complex, across the current railway, is the Mausoleum of Nur Jahan, the empress of Jahangir. She was daughter to Mirza Ghiyas Beg (Itimad-ud-Daulah), a minister of Akbar the Great, and through marriage to Akbarfs fourth son, Jahangir, became a Mughal Empress. One of her nieces, a daughter of Asaf Khan, was Mumtaz Mahal, the chief consort of the fifth emperor, Shah Jahan. From Jahangirfs incapacity by illness in 1622 until his death five years later, it seems that she mightily governed the empire.

She also planned this, her own, mausoleum herself during her life time. She did not place a dome on the tomb as at her husbandfs mausoleum, nor constructed any minarets for embellishment, making it quite modest, though its scale is grand at 38m square. Among the mausoleums of Mughal empresses, it is second only to the Taj Mahal in Agra and the Bibi-ka-Maqbara (Mausoleum of Aurangzebfs wife) in Aurangabad. Returning into Lahore city, one find the most important mosque in the old town area, the Wazir Khan Mosque, so called after the financial contributor, Shaikh Ilm-ud-din Ansari who had the title of Wazir Khan. Unlike the Badshahi Mosque, it is a Persian-type mosque with a courtyard of 40m by 50m firmly surrounded by buildings and four Iwans. The worship hall, as fully wide as the courtyard, has not the usual three domes but five. It is curious that they are double-shell domes despite being shallow ones; what was the effect they were aiming for? It can be said the main feature of this mosque is in its colorful decoration, such as the glazed tiles on its surfaces throughout. As the colors are time-worn now, the mosque has a sober beauty inside and out. The patterns and color combination of its tile mosaics differ from the Persian manner, and tile mosaics are relatively rare in India, so it can be regarded as Lahore style.

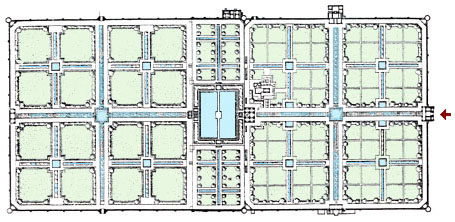

Here too, I was able to climb the northeastern minaret to take a good picture of the mosque. The road on the right side of the photo is the Kashmir Bazaar. Walking along this road about 250m to the Delhi Gate, one can reach the largest Hamam (public bath) in Lahore, the well preserved Wazir Khan Hamam. An enormous garden in the northeast of the city is the renowned Shalamar Bagh (Shalimar Garden), constructed by the architect-emperor, Shah Jahan, at huge expense, under the same name as the largest Mughal garden in Kashmir, India. The principal notion of this garden was to materialize on earth a celestial garden promised to pious followers, depicted in the gKuranh (Koran). The project started with the drawing of water through a canal from the Ravi River, while the garden itself in the site was completed in a year and six months from June 1641. It is considered a masterpiece of Mughal gardens, consisting of two extensive Charbaghs and a large cistern in between, and forming a three-leveled terraced garden with a variety of views. Its total size reaches 300m by 690m. Water flows from the higher right on the plan to the lower left through water channels, and each intersection point makes a square tank.

Plan of the Shalamar Bagh, 1642

A four quartered garden is called Chahar Bagh in Persian and Charbagh in Urdu, spoken in India and Pakistan. It principally indicates a square garden divided into four quarters with water channels or garden paths crossing in the center. In the case of a large-scale garden like the Shalamar, it is necessary to draw water channels more densely to irrigate the entire garden, dividing each quartered garden into four smaller quarters, and then further repeating this pattern. It is theoretically possible to repeat it infinitely; a Charbagh could consist of innumerable smaller Charbaghs.

Shalamar Garden, now and then Unlike tomb gardens, the protagonist in this pleasure garden is water rather than a building. The flow of water and fountains give the garden liveliness, meaning that the land should be inclined. The Shalamar Bagh has a difference in altitude of 6m from end to end, enough to allow it to be composed in three-leveled terraces, not only allowing water to flow through channels but also to cascade over Chadars (textured water chute of stone) in various artistic patterns. When all fountains, more than 400, are operating, it is a magnificent view.

When I revisited here however, in spite of torrential rain the previous July and August, very little rainfall followed and there was no water in the channels, and the water level in the cistern was too low to shoot water from the fountains, presenting a somewhat cheerless atmosphere. The historical site of Hiran Minar (literally meaning Deer Minaret) is near the town of Sheikhpura, 48km northwest of Lahore. After Akbar relocated his capital from Lahore back to Agra in about 1600, his son, the future emperor Jahangir, established a hunting base in a forest near Sheikhpura, making an artificial square lake (or huge water tank gathering rain water and snowmelt) as a paradise garden. One crosses a bridge to the central Baradary (open pavilion), just as in the Golden Temple in Amritsar, India. On this central axis, but outside the lake, stand a minaret despite there being no mosque here. The minaret might have been an observation tower, but from which this place came to be called Hiran Minar too. There is also an independent tower of the same name in Fatehpur Sikri, India.

Hiran Minar at Sheikhupura, now and then

Although it forms a quite simple composition, only a garden pavilion called Daulat Khana in the center of a square lake of 260m by 225m with a bridge thrown to it, the charm of the Hilan Minar is certainly this simplicity; it can be also regarded as a water garden.

I traveled to the Sindh province in southern Pakistan to research the Buddhist and Muslim architectural heritage in Hyderabad and its surrounding area for the first time, many structures of which were reported in "The Antiquities of Sind" published by the Archaeological Survey of India in 1929 during the age of British rule. However, some of them had been unattractively reconstructed or had disappeared and most of them were dilapidated, leaving it difficult to find any appealing remains. The Indus River, flowing through Pakistan from the Himalayas to the Pacific Ocean, is called the Sindh River in Pakistan, the lower basin of which is the Sindh Province (named after the river), which includes the largest commercial city in Pakistan, Karachi, facing the Arabian Sea and inland Mohnjo-daro. Hyderabad is 175km east of Karachi, now connected by a highway for two hoursf driving. Those who read Bernard Rudofskyfs book gArchitecture without Architectsh (1964) must have held their breath, looking at a photo of Hyderabad full of Badgirs, or wind scoop towers, standing like a forest, but one can hardly see them nowadays. Only thing that remains from the Hyderabad Fort is its high impressive ramparts in the midst of the town. The mausoleum of Mian Ghulam Nabi (c.1776) of the Kalhora Dynasty and the two tomb groups of the Mirs (administrators) of the Talpur Dynasty (1784-1843) were not in a good state; much of their finishing materials had peeled off and their domes had become blackened, but restoration work was not proceeding.

In the town of Hala, 56km north of Hyderabad, is the mausoleum of Mahmud Sahib, in its suburb are a mosque and tombs, and in the town of Matiari, on the way to Hara, are the tombs of Hasim Shah and others. All of them are in quite similar degree of workmanship; some are dilapidated or reconstructed, but without notable quality. In Karachi, there are numerous colonial buildings erected under the British rule from the 19th century to the early 20th as in Mumbai or Chennai, India. They are well maintained because of their continuous usage until now. As I had previously researched those nine years before, I revisited some of them with greater leisure this time. Finally I would like to introduce a curious urinal that I found in a restroom in Karachi International Airport. It is unusual that in both sides of it form a granite counter on which one can put personal effects, and furthermore, a small showerhead is attached to the wall. Although it is usual to find a faucet and a bowl in a toilet booth in the Indian and Islamic worlds, this is the first time I found a shower faucet beside a urinal. It is for the purpose of washing the organ after urination. It distinctly shows the hygienic philosophy of Islam.

( 01/ 12/ 2010 )

|