Publiée par W. Boesiger aux Editions Girsberger, Zurich

8 volumes, 23 x 28 cm, each 175-240 pp.

In accordance with Le Corbusierfs wins in important international competitions and publishing his theories about architecture and urbanism, the demand for knowing fully about his total works augmented, and in 1929, when he was 42 years old, his eOeuvre Complètef of his works in collaboration with Pierre Jeanneret for 20 years was published by the editorship of young W. Boesiger. Since this book gained strong support from architects and students around the world, who yearned for emodern architecturef, its continuations would be published every four to eight years. The contents until the middle of the 4th volume are works of joint signature with Pierre Jeanneret and those after that are Le Corbusierfs solo works, and the last volume, the eighth, contains his posthumous works after 1965.

The fifth volume of Le Corbusier Oeuvre Complète, 1946-52.

The sixth volume of Le Corbusier Oeuvre Complète, 1952-57,

The seventh volume of Le Corbusier Oeuvre Complète, 1957-65,

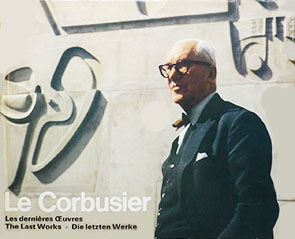

The eighth volume of Le Corbusier Oeuvre Complète, published in 1970,

|